A Spotlight on the Staggering Financial Inequalities in America

Our Manager Tells a Heartfelt Father-Daughter Success Story

07/11/2019

What Is Piggybacking for Credit?

06/27/2020We are at a crossroads in American history.

With the recent killings of yet more Black people at the hands of police, the long-held rage and grief of America’s Black communities have boiled over into nationwide civil unrest and protests demanding justice, equality, and the end of police brutality.

As our nation collectively reckons with its history of slavery and its legacy of violence toward Black people that continues today, we want to shed some light on the economic inequalities faced by Black Americans.

We have already written at length about inequality in the credit system, the shady history of the credit reporting agencies, and the ethics of tradelines, but this time, we feel that it is necessary to focus specifically on racial inequities in our economic systems, with an emphasis on the stories and experiences of Black individuals.

We do not pretend to have all the answers or solutions to these large, structural issues that are deeply embedded within the fabric of American society. However, we feel that it is our responsibility to provide educational resources on these topics so that each citizen can understand the issues we are facing and make informed decisions about how to combat inequality in our own lives and in our society as a whole.

The Racial Wealth Gap

Get ready for this staggering statistic: according to data from the Federal Reserve, the typical Black household has only about 10 cents for every dollar of wealth held by the typical White household.

According to the U.S. Joint Economic Committee, Black Americans are more than twice as likely to live below the poverty line as White Americans, with Black children, in particular, being three times as likely to live in poverty as White children.

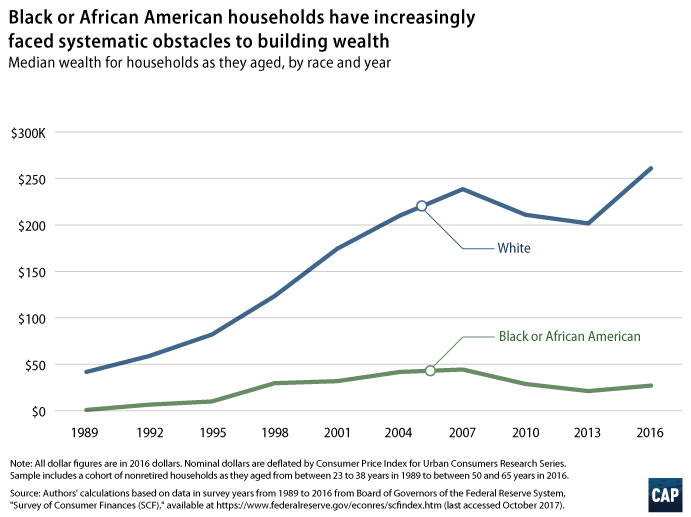

Not only that, but the chasm between Black and White household wealth, instead of getting smaller, is actually getting wider and wider over time, even for Black Americans with higher education.

This chart from the Center for American Progress shows the racial wealth gap widening over time.

Origins of the Racial Wealth Disparity

The racial wealth gap in America has existed from the moment that the first Africans were taken from their land and brought to the colonies in 1619.

For over two and a half centuries, enslaved Black people were used as a source of wealth by White enslavers who claimed them as property, but they had no way of accumulating wealth for themselves. They were forced to work for nothing and were not allowed to keep any of the wealth they generated.

Even after slavery was legally abolished in 1865, that certainly did not create a level economic playing field.

For at least another century, various laws and policies continued to block Black people from attaining wealth, and discrimination is still pervasive today.

Government-Sanctioned Housing Discrimination

Take the National Housing Act of 1934, for example. Passed in the wake of the banking crisis that kicked off the Great Depression, this act created the Federal Housing Administration (FHA). The FHA made it easier for White Americans to afford homes by providing mortgage insurance to protect mortgage lenders from borrower defaults.

Unfortunately, the FHA outright refused to insure loans to Black consumers and even consumers who wanted to live in areas near Black neighborhoods. This practice of “redlining” not only restricted where Black families could buy homes, but it also affected the types of funding they could get and the terms of those loans. (Without FHA insurance, Black home buyers were forced to accept inflated prices and fees as well as predatory contracts pushed by deceitful contact sellers.)

Furthermore, it discouraged investment and development in primarily Black areas, which led to the decline of many communities and of property values in those areas.

While many White families were buying up houses using government-sponsored, low-interest mortgage loans, Black families did not have this luxury, which meant they were shut out of an important opportunity to accumulate wealth in the form of home equity.

Ultimately, the racial wealth gap cannot be explained or fixed by the behaviors or decisions of individual Black people. It is the result of 400 years of structural racism and oppression in America, and solving it likely requires dramatic and large-scale policy changes.

The Federal Housing Administration insured mortgages to help make it more affordable for consumers to obtain mortgages and purchase homes—but only for White Americans.

Employment

The rate of unemployment of Black people is twice as high as the unemployment rate of White people.

Racism and prejudice undoubtedly play a significant role in this, as research has shown that Black people today still face the same amount of hiring discrimination that they did in the 1980s.

The Center for American Progress wrote the following in 2011, when the economy was starting to slowly recover from the Great Recession; however, the information unfortunately still holds true today in 2020, especially in the midst of the COVID-19 recession:

“The unemployment rates for African Americans by gender, education, and age are much higher today than those of whites, and these unemployment rates for African Americans rose much faster than those for comparable groups of whites during and after the Great Recession. The unemployment rates for many black groups in fact continued to rise during the economic recovery while they started to drop for whites…It is now painfully clear that African Americans are still facing depression-like unemployment levels.

…there are unique structural obstacles that prevent African Americans from fully benefiting from economic and labor market growth—obstacles that deserve particular attention when unemployment rates for African Americans stand at the highest levels since 1984.”

In addition, Black workers are more likely than White workers to have low-wage jobs, which leads to Black families having lower average incomes than those of White families. White annual household incomes are about $29,000 higher than Black annual household incomes.

People of Color Are Bearing the Brunt of the Recession

It is impossible to ignore the effects of the economic recession that has begun as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, which is disproportionately impacting Black and Hispanic communities, just like the Great Recession did in 2007 – 2009.

Job Loss

Pew Research Center reports that Hispanic and Black adults are being the most affected by the loss of millions of jobs due to the coronavirus.

This is primarily because people of color are overrepresented in many low-wage jobs within the industries that have had to shut down during the pandemic, such as food service, retail, and hospitality. These are also jobs that cannot be done remotely. Consequently, Black employees are especially vulnerable to being laid off.

Furthermore, not only are Black workers often the first to be let go during recessions, but they are often the last to be re-hired when the economy recovers. According to the Center for American Progress, it’s important to recognize “…that black labor market prospects are hit much harder by recessions and that it takes longer for African Americans to recover from an economic downturn.”

Black workers tend to be the most likely to be laid off during a recession and they are also often the latest to be re-hired as the economy is recovering. This holds true both for the Great Recession of 2007-2009 as well as the COVID-19 recession happening today in 2020.

Business Closures

A study from the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research on the impact of COVID-19 on small business owners revealed that the percentage of Black-owned small businesses that have been forced to close due to the pandemic (41%) is more than twice the percentage of White-owned businesses that have closed for the same reason (17%).

The Paycheck Protection Program, which is part of the CARES Act, was intended to “provide small businesses with funds to pay up to 8 weeks of payroll costs including benefits.” However, some have pointed out that the program is likely to be perpetuating racial inequality by giving the role of distributing funds to banks that have a demonstrated history of discrimination against Black borrowers.

41% of Black-owned small businesses have been forced to close due to the coronavirus pandemic, compared to 17% of White-owned businesses.

Housing Insecurity

Evictions have been temporarily paused in many areas since many renters have lost their jobs during the pandemic and can not afford to pay rent. Once these eviction bans are lifted, however, it is predicted that Black and immigrant tenants will make up the majority of those displaced by the coming housing crisis.

According to Politico, “Black and Latino people are twice as likely to rent as white people, so they would be most endangered if the protection from removal is ended.” Furthermore, Black and Latino households usually spend a greater portion of their income on rent than White renters. Any disruption in income could spell disaster for these vulnerable groups of tenants.

Poor women of color, specifically, are much more vulnerable to eviction than any other demographic group, with one in 17 being evicted each year, compared to only one in 150 for poor White women.

The consequences of having an eviction on your record are severe. It can be nearly impossible to find safe and affordable housing since many landlords refuse to rent to tenants who have previously been evicted. This leads to many low-income Black women being forced into homelessness and dangerous living conditions.

If the landlord passes the bill for unpaid rent onto a debt collector, then it becomes a collection account, which shows up on your credit report and can heavily impact your credit for up to seven years. Similarly, if a landlord seeks a court judgment against you for unpaid rent, the judgment could appear in the public records section fn your credit report.

Credit Difficulties

With less wealth and lower average incomes than White households, Black and Hispanic households are less equipped to weather financial emergencies without getting behind on bills, which is the number one cause of bad credit.

A recent Pew Research study determined nearly half of Black adults surveyed reported that they are worried about not being able to pay all of their bills over the next few months.

For a list of tips and resources on getting through the COVID-19 pandemic with your finances and your credit intact, even if you are having a hard time paying your bills, read “How to Protect Your Finances and Credit During the Pandemic.”

Black and Hispanic families have fewer resources to fall back on in case of financial emergencies, which means they are especially vulnerable to declining credit scores due to late or missed bill payments.

Medical Debt

It is well known that many Black communities deal with higher pollution levels and “food deserts” where access to affordable, healthy foods is often not possible.

And since Black Americans are more than twice as likely to be in poverty than White Americans, they are therefore more likely to experience food insecurity, inadequate nutrition, a lack of healthcare, and the stress of constantly worrying about money on a daily basis.

All of the stressors listed above have been shown to have lifelong consequences on the physical and mental health of poor people, including strong negative effects on the immune system. This means low-income individuals (especially low-income people of color, who also suffer from the effects of “weathering”) are less able to fight off infections and more likely to live with various chronic illnesses that can make the coronavirus more deadly.

As we mentioned, Black workers are overrepresented in lower-wage jobs and more likely to get laid off, which puts them at risk of losing their health insurance coverage or, often, not even having access to health insurance in the first place.

When you put all of these factors together, it creates the perfect storm for Black individuals to get sick with COVID-19, suffer more severe complications that could lead to being hospitalized, and not have the resources to cover extremely expensive hospital stays.

Even if the illness is less severe for some, who may be able to recover after staying at home for a few weeks, they still have to deal with the high cost of missing work while sick and isolated at home. Losing out on even one paycheck can be devastating for low-income households who have not had the option of building up savings.

Naturally, when you combine serious illness with no health insurance and no safety net, the result is massive medical debt. Research has shown that Black Americans are 2.6 times more likely to have medical debt than White Americans and are also nearly twice as likely as White people to be contacted by debt collectors and to borrow money due to medical debt.

When consumers cannot afford to service their medical debt, or if they have to stop paying other bills in order to be able to make their medical debt payments, they will inevitably end up missing payments, defaulting on debts, having accounts go into collection, and possibly even filing for bankruptcy in extreme cases.

All of these derogatory items are severely damaging to one’s credit and therefore tend to make credit more expensive and less accessible to consumers who struggle with medical debt. This impact is long-lasting since negative information stays on your credit report for seven years or even up to 10 years in some bankruptcy cases.

For those who cannot afford adequate healthcare, getting sick depletes scarce resources, limits future opportunities, and stunts financial growth for many years, thus continuing the downward financial spiral.

Medical debt, which was already a severe burden on American consumers, is becoming an even more worrisome issue during a pandemic and a period of extremely high unemployment rates that are disproportionately affecting people of color.

Racial Disparities in the Credit System

Since race and ethnicity are not legally allowed to play a role in credit scores, you might think that consumers of all races would have equal opportunity in the credit system. Unfortunately, however, this is not the case.

If you have read our article called, “What Happened to Equal Credit Opportunity for All?” then you might remember these surprising facts from a report by the Federal Reserve Board:

- Black and Hispanic consumers, on average, tend to have lower credit scores than non-Hispanic White and Asian consumers, even after controlling for other variables such as personal demographic characteristics, location, and income.

- Black borrowers pay higher interest rates on auto loans and other installment loans than non-Hispanic White borrowers who have the same credit score.

- Black and Hispanic consumers experience higher denial rates than other groups with the same credit score.

In addition, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau has also found racial patterns in their reports on credit invisibility.

- Black and Hispanic Americans are more likely to be credit invisible (lacking a credit record) than White and Asian Americans—15% of Black and Hispanic consumers lack a credit record, compared to just 9% of White and Asian consumers.

- Black and Hispanic consumers are also more likely than White consumers to have credit records that cannot be scored by widely used credit scoring models—13% of Black adults and 12% of Hispanic adults are unscorable, versus only 7% of White adults. (The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) did not provide the percentage of Asian consumers who cannot be scored but said that “the rates for Asians are almost identical” to those of White consumers.)

Since credit invisibility and unscorability are more common among Black consumers, it should not be surprising to learn that Black households are more than twice as likely as White households to use payday lending. Payday loans are an expensive and usually predatory type of credit, in contrast to traditional sources of credit, such as banks, credit unions, and credit card issuers.

Black and Hispanic consumers are more likely than White consumers to have a credit record that cannot be scored by commonly used scoring models or to be completely credit invisible.

Credit Options Are Limited by Circumstances

In our credit system, there are some people who have the privilege of starting out with good credit and stable finances simply due to the circumstances they were born into, while many others are not so fortunate.

As we talked about in our article about equal credit opportunity, there are five main factors, referred to as the “five C’s,” that influence a borrower’s performance when it comes to paying back debt:

- Capacity: the amount of income that is available to pay off debts

- Collateral: the value of assets backing a loan, such as your car or your house

- Capital: the value of assets that do not explicitly back a loan, but may potentially be used to repay it

- Conditions: events that can disrupt a borrower’s income or create unexpected expenses that affect a borrower’s ability to make loan payments, such as a job loss

- Character: the financial knowledge, experience, and/or willingness of a borrower that is relevant to their ability to manage financial obligations

As much as some people may like to believe that getting good credit is simply a matter of determination and hard work, in reality, each of the five C’s is subject to external forces and influences that may be beyond the control of the borrower.

When it comes to your capacity to pay off debts, for example, your income may be limited by the availability of jobs where you live and the types of jobs you can qualify for. Hiring discrimination and other challenges prevent many Black individuals from earning to their full potential, which results in a reduced capacity to pay off debt compared to White folks.

In order to have collateral and capital, you need to have valuable assets, which is a privilege that not everyone enjoys.

A borrower’s “character” depends on their upbringing and education, which for many people does not include adequate financial education.

And while anyone could be faced with unexpected conditions that may lead to financial hardship, people who are financially and socially privileged are in a much stronger position to recover, while others who are less fortunate could face financial ruin from even a single emergency.

Lacking Access to Credit Has Consequences

The reality in our country is that centuries of systemic inequality continue to have an impact on all of these five C’s in countless ways, which contribute to higher rates of credit invisibility and poor credit in Black communities.

As the CFPB states, “…the problems that accompany having a limited credit history are disproportionally borne by Blacks, Hispanics, and lower-income consumers.”

For example, data show that 42% of consumers in communities of color have debt in collections, compared to only 26% of consumers in White communities. Delinquency rates or default rates for medical debt, student loan debt, auto loans, and credit card debt are higher for communities of color across the board.

This makes a lot of sense when you think about the fact that Black and Hispanic borrowers have lower incomes and less wealth that they can use to service their debts compared to White borrowers.

The consequences of these disparities are far-reaching. Here are just a few of the repercussions of having no credit or bad credit:

- It is more difficult to obtain credit, from credit cards to installment loans.

- Credit is more expensive—it comes with higher interest rates and fees and may require a larger down payment or security deposit upfront.

- Insurance rates may be more costly for those with bad credit.

- It may affect your employment opportunities since surveys have shown that around 20%-25% of employers conduct credit checks as part of the hiring process for some positions.

Bad credit may be bad news for job seekers since many employers check candidates’ credit reports during the hiring process.

Who Has the Privilege of Receiving Financial Support From Others?

Perhaps another “C” could be added to the list: community.

Often, the difference between good credit and bad credit or no credit at all often comes down to having a strong financial support network.

If you think about the five C’s of credit performance (capacity, collateral, capital, conditions, and character) we described above, each factor can be influenced or controlled by the financial resources available to you within your social circle.

According to the Urban Institute, “Financial support received can be saved or invested in an education or a home and it can be used to cover unexpected costs, helping families remain stable through financial emergencies.”

Having been deprived of generational wealth for centuries, Black households have fewer financial resources to draw on when a friend or family member is in need, and they receive less financial support from those in their networks compared to the amount of support that White families receive.

The Federal Reserve reports that while 71% of White Americans say they would be able to get $3000 from friends or family if they needed to, only 43% of Black Americans could say they would be able to do the same.

Black and Hispanic households are much less likely to receive family inheritances than White families and receive less money on average. This gap in generational wealth contributes to the larger racial wealth gap.

Another example of uneven access to financial support by race has to do with large monetary gifts and inheritances. The same report by the Urban Institute quoted above states that Black and Hispanic families are five times less likely to receive large financial gifts or inheritances than White families.

For those who do benefit from large gifts and inheritances, Black families receive an average of $5,013 less than White families. It is estimated that this disparity explains 12% of the racial wealth gap.

From these examples, we see how a person’s family connections can enhance their access to capital and collateral, which can then make it easier to obtain and successfully pay off credit obligations. Conversely, not having access to those resources and possibly even having to support your own friends and family makes it much more difficult to manage debt.

An article in Forbes about the racial wealth gap summed it up well: “Those who have neither emergency savings nor flush friends and family to tap are more likely to take high-rate loans from payday lenders, skip needed medical care, fall behind on rent, mortgage or other bills or even have trouble paying for food.”

Piggybacking for Credit: Only for “Friends and Family”?

Being part of a privileged community does not only make it easier to access capital. It also means that you may be able to acquire a positive credit history before you have even used credit or opened your own primary accounts, thanks to the help of friends or family.

Achieving good credit early on in life is often the result of having friends and family members who also have good credit and who can share their positive credit history with someone who is just starting out. This process is called credit piggybacking because you can “piggyback” on someone else’s good credit in order to build up your own credit profile.

Ways to piggyback for credit include opening an account with a cosigner or guarantor, opening a joint account with someone who has good credit, or becoming an authorized user on someone else’s tradeline. Becoming an AU on a seasoned account is usually the preferred method for building credit fast because you can add years to your credit history simply by being added to the account, whereas the other methods involve opening a new primary account and waiting for it to age.

Unfortunately, when it comes to credit piggybacking, we see the same patterns of inequality along racial lines.

Many Consumers Are Already Benefiting From Credit Piggybacking

A study on AU accounts conducted by the Federal Reserve Board revealed that over a third of scoreable consumers in the United States have at least one AU tradeline in their credit profiles.

However, when the prevalence of AU tradelines is broken down by race, twice as many White consumers have AU accounts as Black consumers: only 20% of Black consumers have AU accounts, compared to 40% of White consumers.

In addition, the statistics showed that Black individuals have fewer AU accounts, on average, than White individuals, and when Black consumers do have AU tradelines in their credit profiles, the tradelines have less age and higher utilization rates of the tradelines held by White consumers.

What About “Equal Credit Opportunity”?

Despite the fact that one in three scorable consumers in our nation are already taking advantage of authorized user tradelines, there are still some who oppose the tradeline industry because they feel that those who purchase tradelines are “cheating the system.”

Yet these same people and institutions usually have no qualms about recommending that parents help their children build credit by allowing their children to be authorized users on their credit cards, or that a spouse who has good credit designates their partner as an authorized user for the purpose of building credit.

Most, if not all, of the big banks promote this strategy, often even explicitly saying that the authorized user does not need to be given the card to use, which makes it clear that it is solely for the purpose of getting that tradeline to appear on the authorized user’s credit profile.

As you can see, just like in many other aspects of our society, there is a double standard when it comes to who is “allowed” to benefit from AU tradelines.

While the banks publicly encourage their customers and their customers’ “friends and family” to use this credit-building tactic, they also claim that this opportunity should not be available to others who turn to the tradeline industry because they simply do not have the option of going to family or friends for credit help.

It does not seem fair or equal to promote a powerful credit-building strategy for those who are already privileged enough to have support from their social network while at the same time saying that it is wrong or should not be allowed for those who have fewer opportunities to get ahead.

How Can We Create Equal Opportunity for All?

Unfortunately, the racial economic divide in this country runs deep, as it has been perpetuated by American systems for generations.

For this reason, Black consumers disproportionally struggle with low incomes, less wealth, poor credit or no credit, and fewer opportunities to get ahead in life financially. This makes it more difficult to simply pay the bills and stay afloat, let alone to save money, invest in assets, and build wealth.

So what can we do to start to bridge the divide?

To address the disparity fully, it’s clear that large-scale economic policy changes on a national level will be needed.

The actions of individual consumers and businesses, while they cannot solve the problem as a whole, can help people take steps to improve their finances and credit.

Education on the Credit System and Personal Finance

Sadly, basic financial education is not something that most people are exposed to, neither in school nor at home.

Research is mixed on the topic of whether enhanced financial education in school would significantly help with the issue of economic inequality in our country. However, it can make a big difference to individuals to educate themselves on money management and the credit system and become empowered with this information to make better financial decisions.

We understand the importance of being educated about credit, knowing what the weaknesses in the credit system are, and understanding the steps you need to take to improve your credit. When you become familiar with how the credit system works, you have more power to make it work for you, instead of the other way around.

To help consumers learn about these topics and take action in their own lives, we have created a comprehensive Knowledge Center that contains information on tradelines, credit repair, credit scores, the legality and ethics of using tradelines, and more.

You can start taking control of your financial future with the knowledge and the power of these resources at your fingertips.

Tradelines and Equal Credit Opportunity

For those who lack a positive credit history, there are not many options to get started on building their credit profile, since most lenders base their decisions on your credit score and your track record of successfully managing credit in the past. Just like trying to get a job with no work experience, It can seem nearly impossible to get credit if you have not already had experience with credit before.

This is why we are so passionate about what we do at Tradeline Supply Company. We fill the void that so many consumers are looking for in their quest to start building or rebuilding their credit.

Our goal is to help create equal opportunity by making tradelines affordable and accessible to all consumers, not just the wealthy and the privileged.

Conclusion

While the wealthy have always had easy access to credit and strategies for building credit, the same cannot be said for the many people in America who are on the other, less fortunate side of the massive wealth gap.

At the same time, income inequality and the racial wealth gap keep growing larger, leaving more and more people behind who are struggling to build credit, manage their finances, and create a strong financial foundation for themselves and their families.

Systematic, government-legitimized discrimination against Black folks deprived Black communities of the opportunity to grow and thrive economically for hundreds of years. To this day, even though we claim to value equality, there are serious financial disparities in our systems that Black families bear the brunt of.

Although we alone cannot repair this injustice, we will continue to do our part in helping to provide equal opportunity to all consumers and create a more level playing field in our economy.

Additional Resources

What Happened to Equal Credit Opportunity for All?

What Does It Mean to Be Credit Invisible?

Vox – America’s wealth gap is split along racial lines — and it’s getting dangerously wider

Center for American Progress – Systematic Inequality: How America’s Structural Racism Helped Create the Black-White Wealth Gap

Joint Economic Committee – The Economic State of Black America in 2020

realtor.com – The Surprising Ways Race Remains a Factor in Mortgage Lending

Vox – Living in a poor neighborhood changes everything about your life

National Consumer Law Center – Past Imperfect: How Credit Scores and Other Analytics “Bake In” and Perpetuate Past Discrimination

Center for American Progress – The Economic Fallout of the Coronavirus for People of Color